Soldiers win medals for bravery in the face of the enemy, or for a particularly brilliant piece of leadership, or for a conspicuous exploit which materially affects the course of the conflict. Everybody accepts the convention and understands the reasoning behind it.

As with so many other things, it is not new. Men were being similarly rewarded by their masters as far back as recorded history goes. An intrepid soldier gains promotion; a resourceful slave who rescues his owner from danger wins his freedom; a champion is rewarded with the property of the opponent he has just overcome in single combat. And so on.

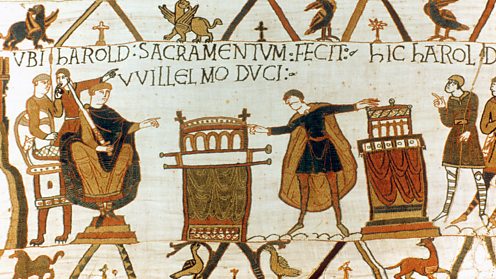

The Normans did it like everybody else. Look at the panels showing the end of William`s Brittany campaign. Remember Harold rescued two Norman soldiers from the quicksands of the River Couesnon.

My guess is that he did rather more than that during the summer when he was half-guest and half-prisoner of the Duke. A man of Harold`s rank, personality, and background could not have sat by and done nothing. Harold participated, and William had enough sense to see that a campaign was a campaign, and that Harold would have something to offer. These two men were lifetime soldiers; they saw each other in action; they came to respect professionalism in each other. They knew what each other were capable of.

Harold understood perfectly well the danger he was in; the two chief protagonists who coveted the throne of England were together under the same roof for several months, and one of them was the guest of the other; he was alone (well, apart from a handful of falconers and sailors who had survived the shipwreck) – alone in a land and a court brimming with foreign soldiers and barons, all of them with an eye to the main chance.

At the same time, they too recognised talent when they saw it. Harold moreover seems to have had, like most successful leaders, a knack for getting the best out of fighting men, and that skill can cross frontiers. Not many generals would have risked their lives fishing foreigners out of quicksands. Campaigns bring men together. It seems more than likely that the Norman troops came to think well of him. It is more than possible that both William and Harold developed a healthy regard, even a measure of friendship, for each other.

So the award of knighthood to Harold, once Count Conan had had his knuckles rapped, could well have been as much personal as political.

A twenty-first century reader of this account would have nodded in understanding. But an eleventh-century man would have seen it in a different light.

A man who is created a knight today gets a gong, an investiture by the Queen (if he`s lucky), and his name in the paper. A knight in the eleventh century had a solid place in feudal society – the institution which ensured (for the most part) that every man had a lord above him, and, with rare exceptions, some inferiors below him. It was a contract; it was a bond. The Latin word for ‘bond’ was feudum. Hence the ‘feudal system’. It wasn`t in fact very systematic, and there were endless variations, modifications, and exceptions. But it was what held medieval society together, at any rate in western Christendom. Everybody understood what the bond signified: the man above guaranteed protection, and the man below promised service of one kind or another. It was moreover a public bond; there were as many eye-witnesses as the organisers could muster. In a society where the vast majority could not write, what mattered was not what they read, but what they saw, with their own eyes. There was no room for misinterpretation.

So what William had done was not simply to pat a brave fellow-commander on the back; he had shown that Harold, in full view, had accepted him (William) as his feudal overlord. If he should go back to England now and seize the crown when (God forbid) King Edward should die, he would be guilty of the worst offence in feudal society: breaking his oath of loyalty to his feudal superior.

Remember the Normans` fondness for chess. Time and patience; patience and time. Harold, by virtue of his shipwreck, was already a nobody, a piece of flotsam thrown up by a capricious Channel. He had become indebted to William for rescuing him from the clutches of Guy of Ponthieu, who thought only about ransom money. Throughout the summer he was a guest of his rescuer, and so owed him for bed and board. And to all intents and purposes he was also a prisoner. We know of no attempt he made to request, demand, or steal a boat to get home on.

By taking advantage of the Brittany campaign, and awarding knighthood, William had given himself the chance to put Harold in a worse position of subservience. (Who knows? Perhaps he had even stage-managed the whole campaign, or brother Odo had thought it up.)

In itself, it wasn`t going to get William much further forward – well, not then. But opportunities could come from anywhere, and the fact that Harold was now to be seen as a kind of subordinate could put him (William) in a very advantageous position when he needed evidence to put Harold in the wrong.

William was planning to steal somebody else`s country, so he was on the lookout for any scraps of justification he could get.

Incidentally, Harold must surely have understood the significance of all this, but, in his position of half-guest and half-prisoner, he had little choice but to go along with it. In the game of one-upmanship they must have both played during that summer, it would not do for Harold to show that he was in any way put out. The more he serenely went on his way, the more the Normans must have scratched their heads and wondered what the Devil he was really up to.

Recent Comments