There is in print somewhere (I forget the details) a book devoted solely to the deaths of the kings of England. Not just the fact, or the date, or the place, or the circumstances, but the actual medical causes and symptoms. Pretty grisly it is too. Consider the level of medieval medical knowledge, and the extent to which the practice of medical science was influenced – even at times governed – by charms, magic, astrology, superstition, an over-watchful Church, old wives’ tales, witchcraft, and any other mumbo-jumbo that comes to mind. Consider too the level of ignorance then about hygiene, poison, antiseptics, anaesthetics, drugs, and microbes generally. It’s a wonder that anybody who fell ill survived.

Harold`s case was different: not unique, but at least out of the usual run. Everyone knows that he died in battle. Like Richard III. Their deaths were still as messy as the other royal endings just referred to, but there is a simplicity and ordinariness about them which aids understanding. In a wry, back-handed sort of way, they are more satisfying. No loose ends, over and done with, no doubt, end of story. Yes, we get that.

Trust the historians to come up with something which throws the whole thing into the air again.

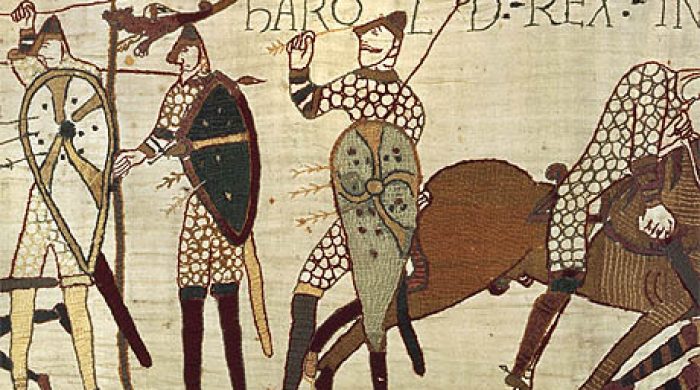

They have fastened on to the fact that the part of the Tapestry which shows Harold`s death involves not one Saxon figure but two – and we don’t really know which one was meant to be Harold. The first figure is standing, holding his shield by the left arm as usual, With his right hand he has grasped an arrow which appears (very clearly) to be sticking into the rim of his helmet Above the figure are the words in the frieze: ‘HIC HAROLD REX’ – which would appear to be pretty conclusive. (‘Hic’ means ‘here’.)

And yet – Harold here does not appear to be in distress. He is simply yanking out a nuisance. He is also sufficiently in command to be able, with his shield hand, to retain control of his spear. Other men struck lose their grip; the weapon falls, as shown in the very next picture. Incidentally, you can`t see the arrow, because nine hundred years of wear and tear have completely eroded the stitching. All that is left is a row of tiny needle-holes. Admittedly in a straight line, and pointing to the rim of the helmet. But it takes quite a leap of the imagination to assert that the arrow has gone actually into his eye.

Where the Tapestry shows other men struck by sword, arrow, or spear, they are very clearly smitten – falling, stumbling, reeling, their weapons falling from their hands. Where men are shown struck in the eye, the arrow is very clearly sticking right into their eye. No argument.

Now the second figure. This man is falling, visibly suffering from a death wound. His axe has flown from his hand. A triumphant Norman horseman looms over him, slashing the King`s thigh with his sword. The words in the frieze directly above say ‘INTERFECTUS EST’ – which mean ‘he was killed’.

It is even possible that both figures were meant to be Harold. Work that one out. They had artistic licence in the eleventh century too.

We are also told in the chronicles of the battle that, at the end, a small knot of desperate Norman knights hacked their way through the remains of the shield wall and cut Harold down, Which makes sense. The body was so mutilated that Harold`s mistress, Edith of the Swan Neck, could not recognise his face when she searched the field after the battle. She only knew because of certain moles on the body which only a lover would be aware of. Nevertheless, stories like this – the arrow in the eye – show a great reluctance to go away. Part of the reason for this may be that when we first learned about it we were at primary school, and stories learned young push down deep roots, perhaps because the soil of our young imagination and memory is so fertile. Even if we know in our heart of hearts that the tale is probably wrong, we still like to hang on to it – just in case some other evidence turns up to rescue it.

Recent Comments