If the Tapestry isn’t about the Battle of Hastings, what is it about?

It is about the Battle of Hastings, but it’s about a lot of other things as well.

Such as?

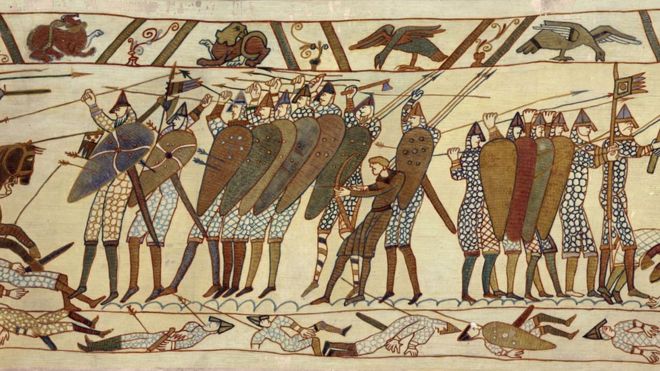

The Tapestry is divided into 43 panels, so numbered for the convenient sake of reference. It is in fact one continuous piece of embroidery, obviously stitched together in segments. No needlewomen could work simultaneously at a piece of material over two hundred feet long. But the whole piece is intended to be presented as one piece, one ‘document’.

A book contains separate pages. When you have read one, you turn over the page. You, in effect, move the book. With the Tapestry, it doesn’t move; you do. It was meant to be gazed at as you walked past. That is precisely what a tourist would do today if he visited Bayeux in order to see it. It was designed to be put up on the walls of a hall. We think it might have been commissioned by William’s half-brother, Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, possibly to decorate the walls of his cathedral.

That doesn’t answer the question.

No, it doesn’t. But we have established its size. Now let us try some arithmetic. The Tapestry, as we said, has 43 sections. Out of those 43, only 7 describe the battle. And the battle doesn’t start till section 36.

What’s going on then in the rest of it?

All sorts of things. We could give you a list of topics depicted in the other panels: for example, the old King, Edward the Confessor; his chief adviser, Harold, Earl of Wessex; the King’s death; Harold’s shipwreck off the coast of Normandy; his time spent as a guest (possibly a sort of polite prisoner) of Duke William; his presence at one of William’s summer campaigns, in Brittany; and so and so on – a great deal more.

But that might serve only to confuse. It would swamp you with facts. What is important to understand is the purpose, the intention, the aim, of the whole Tapestry. It was a huge piece of public relations on the part of the Normans. That is what holds the Tapestry together, dramatically. If the battle takes up only 7 out of 43 panels, the Tapestry clearly is ‘about’ something else.

All right then – what?

Have you ever noticed that in politics, in whatever age, those who have done something big are very anxious to show the world not that they have done something (everyone can see that), but that it was the right thing to do. Listen to party political broadcasts. Read the memoirs of retired soldiers and prime ministers. Look at the manifestos (or it is ‘manifestoes’?) of election committees. One chieftain defeated by the Romans commented wryly that, if you believed what they said, they conquered the whole world in self-defence.

If you are about to embark on a course of action which in almost everyone else’s book of commandments is, at best questionable, at the worst criminal, you take great pains to establish that what you are doing is right, correct, sensible, even honourable.

Duke William was planning to invade, conquer, and rule a sovereign foreign state. So he needed a lot of plausible reasons.

First, he had once visited England, in 1051, and during that visit, he claimed, the childless King Edward had promised him the crown on his (Edward’s) death. Never mind whether it was true; William said it was. If his invasion had failed, nobody would have taken any notice except to laugh at him. But, as he succeeded, he could use this to ‘prove’ that God looked kindly on his invasion to claim what was ‘rightfully his’.

So he had had this project on his mind for ages.

He spent the years following his visit clearing the decks in Normandy, and waiting. Then he had a piece of luck: in 1064 Harold was shipwrecked off the coast of Normandy. The Normans were not quite sure what to do with him. Even William drew the line at murder; it would have been almost impossible to say that that was the right thing to do.

What is all this to do with the Tapestry?

We are getting there. How would it be, said Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (remember him?), if Harold were to swear an oath to the effect that, when King Edward (God forbid) died, he (Harold) would assist William in securing the Crown of England?

That is what happened (never mind the details for a moment). Harold swore the oath (possibly at Bayeux, but we don`t know for sure).

That was the centre, the hinge, the crunch, the defining act of the story recorded in the Tapestry. And that panel comes smack in the middle of it. Number 24 out of 43.

Why?

Because Harold went and took the throne when Edward died, so he had broken his sacred oath, so he was a perjurer. And God punishes all perjurers. It’s like the old playground mantra that ‘cheats never prosper’.

William thus contrived to show that Harold was a sinner, and merited Divine punishment. The whole Tapestry is a sort of cautionary tale about the wages of sin. The battle, to a certain extent, was incidental. The important thing was to ‘prove’ that Harold was a perjurer. William even persuaded Pope Alexander II to provide a papal banner under which William and his army of righteous crusaders were to carry out God’s Will of inflicting holy punishment on the sinner. William had contrived to recruit the best ally of all – God .

An enemy’s place was in the wrong.

But, surely –

Yes, I know, there is a lot more to it than that (there always is). Perhaps next time…

Recent Comments